The first sign of trouble was the slapping sound of helicopter blades not far above the roof.

“Look,” said my brother-in-law, Alan, lifting his head toward the windows at the back of his house, indicating the brown hilltops about a quarter mile away.

A cloud-head, black at its core, puffed out from between the hillsides, and my first brief instinctive thought was that a thundercloud was going to bring a downpour.

It was smoke. I was in a corner of the San Fernando Valley, at the edge of the Woolsey Fire a day or so after it started, Nov. 9, 2018. Unlike the fires in the forested areas of California, the Woolsey Fire has been feeding mostly on grasses and bushes and small, gnarled trees. It has charred much that is in between Simi Valley and the Pacific Ocean, including Calabasas, Agoura Hills, the Santa Monica Mountains and Malibu. So far the Woolsey Fire has claimed 98,362 acres and three lives. The catastrophic Camp fire to the north has burned through more than 149,000 acres and killed 79.

Do Californians build any differently than in rain-soaked Seattle or humid New Orleans? They most definitely do.

That day, I rounded the corner to Roscoe Boulevard, walked a block and crossed Valley Circle Boulevard, where the full irony of California living was on display. Not an eighth of a mile from the flames, and with winds blowing hard enough to rip the hat off my head, carpenters hammered away on the frames of new houses (starting price: $1.03 million) and a backhoe operator sculpted the hillsides. In fire country, they don’t stop working just because a historic blaze is leaping over the arroyos and crawling up the ravines or because helicopters are dropping flame retardant.

Do Californians build any differently than in rain-soaked Seattle or humid New Orleans? They most definitely do. Maps delineate the wilderness-urban interface, classified by percentage of vegetation. Californians have been moving in to the interface in greater numbers over the recent years. Building codes that cover many fire-prone areas require builders to install fire-resistant roofs, covered vents and chimneys to block embers and ignition-resistant non-combustible eaves, soffits, fences and decks. Guidance for homeowners also recommends leaving 10 feet of clearance on both sides of any access road and landscaping only with low-lying plants with strong root systems. Other guidance suggests spacing plantings more widely on higher-grade slopes. Older structures, built before the newest codes, however, are exempted from fire-resistant requirements—and that’s a lot of houses.

Fatalistic Approaches To Fire Country

There are other, more fatalistic approaches to living in fire country. I met an evacuee who lived in a mobile home on high ground above a nearby canyon, a man in his sixties who operated a garden supply business. He and his wife had had to evacuate their home several times before because of fire danger. Yet, he was calm. He said he insured the home for $50,000 (and the contents for another $50,000). The difference with this monumental fire, he added, is that he saw no firefighters battling the flames on the ground nearby. If it goes, it goes. “We’ll just have to start over,” he said.

|

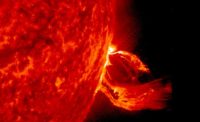

| A helicopter drops flame retardant on a fire in the background and not far from a new home development on the fringe of the San Fernando Valley. |

There’s a peaceful grandeur to life in the hills, and the higher up you live the greater the cushion of quiet between you and the hectic suburban valley floor. Instead of cars, you hear birdsong. But the threat of fire is part of that life, too. When big fires come and the hilltops glow orange in the night, as they did last week (and climate change and more houses mean that will happen more often), the people living in the hills shut their windows against the sooty smoke, sloppily pack suitcases to leave near the front door and wait for the evacuation updates to explode in their mobile phones.

Generations from now Californians, who have always been innovators, will finally understand that the building codes are a feeble stopgap against even more deadly firestorms and that the only permanent solution for fire country, where burning is part of the natural order, is to live away from the fire-prone lands and leave them to enjoy as parks and vacation destinations. For that to happen, the government must create incentives to knock down the old houses and reward building new houses a safe distance from the dry flora that thrives in the chaparrals, so that a fire sparked by any cause no longer triggers mass evacuations and so much costly destruction.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment