For six years Katerra Inc. claimed to be the pioneer of a construction industry future that would be more industrialized and technologically astute.

Now the innovative company's bankruptcy leaves a more traditional legacy: unpaid creditors. How much they will collect of what's owed them is unclear.

Katerra's bankruptcy filing in federal court in Houston states that the company owes $1.29 to $1.55 billion, with from $50 million to $75 million classified as trade payables owed to contractors or suppliers. Another $677 million in the company's complex capital structure is listed as obligations to sureties that may seek indemnifications, and another $22 million is outstanding in letters of credit.

In a statement published June 6, the Menlo Park, Ca.-based company it will keep operating with $35 million in debtor-in-possession financing from SB Investment Advisers (UK) Ltd. and that its projects will proceed followed by an "orderly wind down of its business.” In a declaration to the bankruptcy court, Marc Liebman, the executive now in charge of the company, said Katerra would wind down work on 82 projects that represent two out of three dollars of all of Katerra's expected future revenue. Exactly what was meant by the words "proceed" and "wind down" isn't fully explained.

After the top three creditors, 29 other contractors and suppliers are each owed between $1.4 million and $4 million.

Numerous creditors now may have to await court rulings to collect money they are owed. According to Katerra's bankruptcy court filings, the three creditors owed the most are Grand Rapids, Mich.-based Stiles Machinery, which provides equipment and control systems; Haddad Plumbing & Heating, Newark, N.J.; and Thyssenkrupp Elevator Corp., Atlanta. Katerra owes each between $4 million and $6 million, according to the company.

Twenty-nine other contractors and suppliers are each owed between $1.4 million and $4 million.

In its bankruptcy court filings Katerra lists Liberty Mutual as a workers' compensation insurer and Merchants Bonding Co. and One Beacon Surety Group as surety providers. It isn't clear what type of insurance was provided by several other listed insurers and reinsurers.

Founded in 2015 by Michael Marks, Jim Davidson and Fritz Wolff, Katerra leaders said the firm would "help transform construction through technology." Marks served as CEO until last year.

Katerra had $1.5 billion in revenue last year and offices and operating units across the U.S. and as far as India, China and the Middle East (the company's international units are excluded from the bankruptcy). Its operations included design, manufacturing and construction, primarily of housing. Liebman, previously the company's chief transformation officer, said in his declaration that Katerra had burned through $3 billion in financing but had never made a profit.

Unprofitable Projects Cited in Bankruptcy Filing

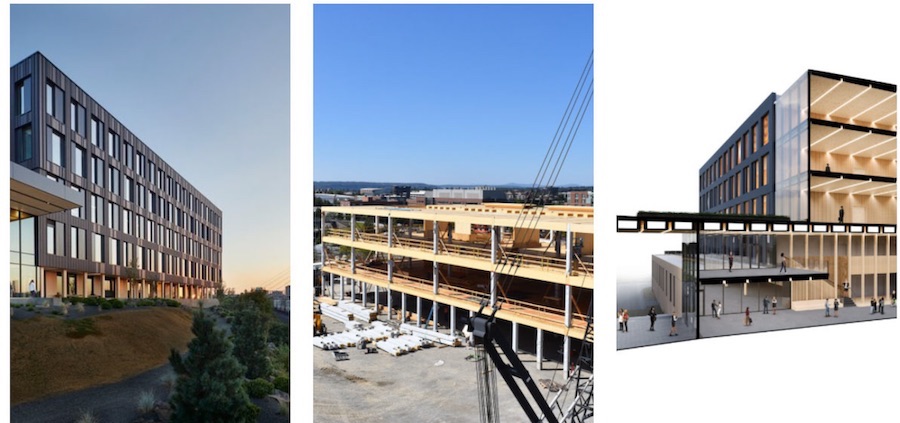

While he described Katerra's numerous innovations in factory production and mass-timber construction, Liebman blamed the company's demise mostly on project cost overruns and losses and discounts given to legacy clients.

Although detailed information about projects and losses is not public, what went wrong now is a subject of much reflection.

Tom Hardiman, executive director of the Charlottesville, Va.-based Modular Building Institute, says he had no specific insight into the company's management practices. But he speculates it took on "too many markets in too big a geography" instead of focusing in a few areas.

Innovation in modular of factory-based construction needs to be done "on an incremental and gradual basis," says Hardiman, especially given the state-by-state differences in regulations that relate to off-site construction.

Katerra Promised Integration and Speed

Others wonder if Katerra's approach to innovation was fundamentally flawed given the gradual pace of change in the industry.

"Construction is changing itself, slowly, piecemeal," says Mathew Aitchison, professor of architecture at Monash University and chief executive of Building 4.0 CRC, an initiative to update the construction process. "What Katerra offered, indeed the hope it held out to the rest of the industry, was integration and speed. It promised to finally pull together the various point-solutions and fragmented baskets of innovation into one coherent venture."

Aitchison, who is based in Melbourne, Australia, says he isn't sure tech investors of the type that founded Katerra "are so forgiving of slower timelines for commercial return."

"I tend to think they were simply repeating a mistake that has been made many times before in attempts to transform building," he says.

And, in Aitchison's view, there are no silver bullets when it comes to construction innovation.

"I tend to question whether there is even a best practice as found in other sectors," he adds. "Instead, there are just endless choices and really hard decisions that require enormous amounts of detailed knowledge from inside and outside the industry. Ideas are the easy part."

This story was updated June 11, 2021 to include thoughts from Mathew Aitchison.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment