A $185-million project will use thermal energy from nearby sewer pipelines to heat and cool seven buildings on a new 250-acre academic campus in Denver.

Although heat recovery systems using a variety of sources—including biomass, solid waste, and wastewater—have been around for decades, this project, at Denver’s National Western Center, represents one of the largest applications of using wastewater as part of a district energy system in the world, says Len Dorr, senior vice president, energy, at AECOM, which is partnering with Denver-based Saunders Construction to design and build the project. “If it’s not the biggest, it certainly is one of the biggest in North America.”

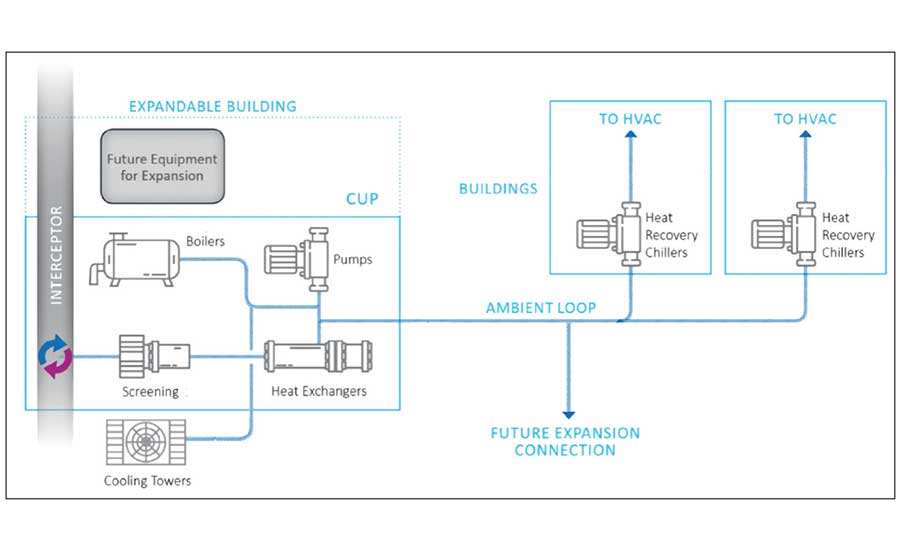

The system will supply a little more than 90% of the campus’ heating and cooling needs. It will use heat exchangers to transfer heat from wastewater in a large sewer pipe to a campus-wide ambient loop. A central plant will then pump warm water to a group of several buildings on campus. The system will help the National Western Center avoid emitting an estimated 2,600 metric tons of CO2 annually.

EAS Energy Partners announced it had closed the deal on an energy partnership with Denver’s National Western Center on Aug. 4. The team is led by Enwave, a Toronto-based provider of district energy systems. Enwave will provide upfront capital and manage the system on campus for 40 years.

The project will include construction of a 72-in.-dia interceptor diversion, one heat exchanger and pumps to transfer heat between the heat exchanger and the ambient campus-wide piping distribution loop.

The National Western Center Authority, which operates the campus, will pay for the system over 40 years with event revenue and monthly energy bills from system users. The Metro Wastewater Reclamation District and the Denver Dept. of Public Health and Environment are providing additional funding.

Energy efficiency advocates have identified district energy systems, in which a central plant powers a small group of buildings in an integrated system, rather than using chillers and boilers in each building, as an effective approach to enhancing energy efficiency and reducing reliance on fossil fuels for heating and cooling commercial buildings. In a 2015 report, the United Nations Environment Programme concluded that widespread adoption of district energy systems in cities, combined with other efficiency measures, could provide as much as 58% of the CO2 emission reductions required in the energy sector by 2050 to keep global temperature rise to within 2° to 3° C.

Shanti Pless, researcher, V-Mechanical engineering at the Dept. of Energy’s National Renewal Energy Laboratory (NREL), says although district energy systems are “pretty common” in Europe, they have yet to take off in the United States. “It works really well when you’ve got one owner of multiple buildings on a campus,” he says.

But it becomes problematic when multiple buildings owned by different private developers try to share an energy system, he says. Among the challenges are the potential for legal disputes among different developers, as well as concern over “phasing issues,” or the ability to finance projects without revenue from future commercial building tenants, Pless says.

Nick Perreten, senior vice president of corporate development at Enwave North America, notes the project is scalable, so that over time, more energy could be drawn from the sewer pipes for additional buildings on campus.

Brad Buchanan, CEO of the National Western Center, says the center is committed to finding sustainable solutions to reducing carbon emissions. “Knowing we’ll have to heat and cool our buildings one way or another, we chose an innovative, clean-energy system that virtually makes something from nothing.”

Design is at 30% completion for the central plant; 100% for the ambient loop as of July 30. Construction is expected to begin in May 2021 and complete in April 2022.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment