Chances are, anyone who’s built in a growing community knows that some local authorities approach new development more thoughtfully than before.

Building codes are modernizing. New rules are written. You can’t just plop a building on the dirt.

Planned Unit Developments (PUDs) are one example of this evolution. While these instruments mean well, they also inject new challenges to construction projects that owners, builders and local authorities must work together to address.

So what’s a PUD? How do they work? And what can owners do to get past the obstacles they impose?

We’re glad you asked.

What’s a PUD?

PUDs are a legal framework communities use to shape the nature of new development.

Call them building codes on steroids.

Because any community’s priorities and circumstances are totally unique, no two PUDs are alike. But they do have much in common with similar instruments like HOAs, TIF districts or special business districts.

For anyone considering building inside a PUD, the framework spells out additional requirements they must meet before local authorities will allow them to build.

Some criticize PUDs and similar instruments under the belief that they restrict how owners can develop land they own. Others praise them for their adoption of a more holistic and harmonious view of communities and the built environment.

That latter point is often the rationale local authorities use when they create a PUD. Combatting urban and suburban sprawl is the most popular goal.

Development, they argue, is good. But it must also be sensible.

What do PUDs enforce?

Well, a lot.

Think of PUDs as building code add-ons applied to small geographic areas. They can dictate a wide range of regulations according to a community’s vision for a neighborhood, block or even street corner. Consider these common enforcement elements:

Building size and orientation – A PUD can dictate how a structure occupies its property. This can include mandating a specific setback from roads or sidewalks and requiring public sidewalk accessibility to a main entrance. PUDs can also enforce building height, either keeping the height of certain kinds of buildings low or requiring that mixed-use developments reach minimum heights to encourage greater density.

Integration with public transit – In areas served by public transit, a PUD can require easy access to bus stops and light rail stations. Many communities additionally consider walking and biking trails as “transit” and can require integration with that infrastructure, too.

Traffic management – To minimize traffic congestion associated with sprawl, PUDs often set added requirements about how a development is accessed by motorists. This can include requiring more entry and exit points and dictating the amount and placement of parking spaces.

Emergency services – Communities experiencing rapid development tend to notice that their emergency response services are stretched thin (and are usually slow to catch up). To combat this, PUDs can require new developments to implement more robust fire suppression systems and provide enhanced access to fire hydrants.

Building materials – Even the materials used to build a structure can be partly dictated by rules within a PUD. This can take shape in many ways, but here are three:

- Communities that prioritize environmental friendliness can require structures to meet LEED standards and mandate the use of low-carbon footprint building materials (in California, for instance, new single-family homes built starting in 2020 must include solar panels)

- To spur greater local or regional economic growth, communities can require a certain percentage of building materials be sourced from providers located in the state where something is built

- To sweeten the deal, some authorities agree to waive the sales taxes on construction materials locally or regionally sourced

The role builders play

Building within a PUD is an intensive and deliberative process. This is compounded by requirements for more rigorous community input.

That translates to hours of additional meetings where owners and communities must receive public comment and potentially adapt plans to satisfy the concerns of nearby residents or neighboring businesses and organizations.

It’s a whirlwind of submittals and re-submittals of proposals. Approval can take months. Sometimes, authorities will carve out exceptions if you cannot meet certain requirements—provided you can clearly document why it’s necessary.

Contractors sit in the middle of it all. Because they’re the most familiar with the specifics of a planned development, they act as the liaison between owners, local authorities and the community at large.

It’s a game of 3D chess that builders must know how to play. And in our view, Design-Build firms have a distinct advantage.

When the design and construction disciplines are confined to a single entity, development approval is much more streamlined. Rather than separate architecture, engineering and construction representatives taking up space, time and money in the process, the Design-Build method produces a single, fully unified team.

Case study: Anderson Hospital’s Goshen Campus

Anderson Hospital’s new ambulatory surgical center in Edwardsville, Illinois provides a textbook example of how building within a PUD should work.

Completed in mid-2020, the 18,331-square-foot facility was the first successful delivery inside a PUD created under the Madison County I-55 Development Code. More development is planned for the site, but here’s how the guinea pig project got done:

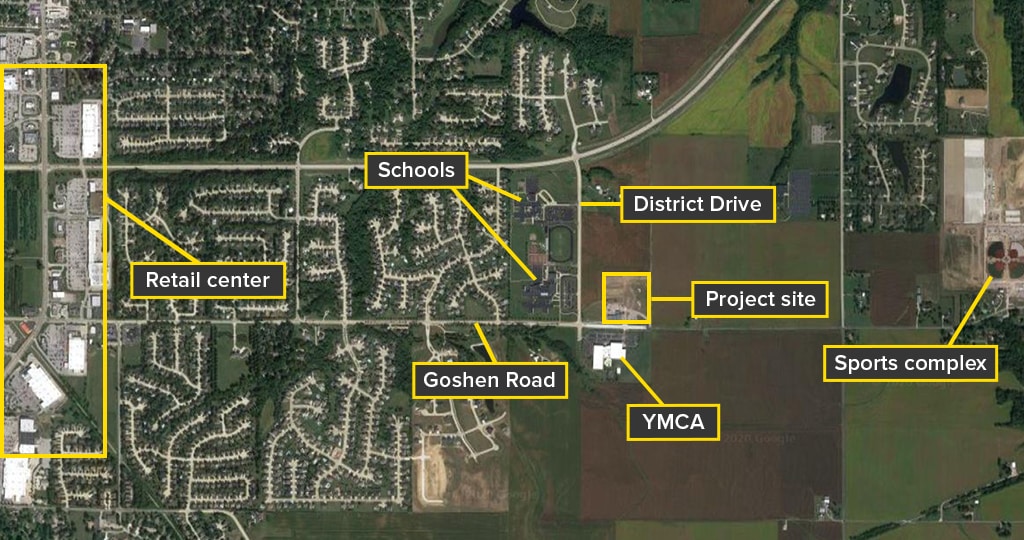

Study the area around the intersection of Goshen Road and District Drive in Edwardsville in the image below. The project site is within the I-55 Development Code territory and is roughly equidistant from the town centers of Edwardsville, Glen Carbon and Troy.

These outskirts of the St. Louis metro are changing quickly. As new subdivisions crop up, other services have followed. The site is adjacent to two schools and a YMCA. A mile and a half west of the site is a major retail corridor where patrons can access local public transit. A sports complex is located a mile east.

The City of Edwardsville, among the fastest-growing in the state, had annexed the site. In concert with Madison County, local leaders there have been quite active in adopting development codes that attempt to reverse obvious suburban sprawl.

To that end, consider how local PUD requirements influenced two key design elements of this facility:

First, the code required the facility’s parking lot be off-street, but it also mandated two points of entry. The building has two entrances—one with access to off-street parking and another fronting Goshen Road—and a wide corridor connecting them.

Second, the code mandated that 40% of the building’s exterior be windows. Our designers realized the obvious patient privacy concerns this raised, so the interior of the facility was designed with back-of-house circulation around its perimeter.

Turn challenges into opportunities

Some see PUDs and other similar instruments as intrusive and burdensome. Others applaud the thoughtful ways they can shape the communities we share. Our experience building in PUDs is proof that development and community action can coexist.

Sometimes that’s hard, but the important things are never easy.

With expertise from the right Design-Build team, owners can connect with local stakeholders to deliver new development where everyone wins.

Our team can show you how to make it work. Let’s talk.