by Viken Koukounian, PhD, P.Eng., and Niklas Moeller

Background sound is an intrinsic part of our daily experiences, yet its fundamental role within the built environment can often be overlooked. This omission is most apparent in noise mitigation projects where the building professionals exclusively rely on the absorptive materials and partition assemblies and, hence, performance indicators such as the noise reduction coefficient (NRC), sound transmission class (STC), and the noise isolation class (NIC)—none of which provide insight into occupant experience of sound in that space.

In other words, this singular focus on objective physical acoustics fails to consider the human (psychological and physiological) component—specifically, that occupants can perceive a space with a higher controlled level and spectrum of background sound as ‘quiet.’ As a result, organizations forgo opportunities to significantly improve acoustical privacy and satisfaction and realize labor and material savings engendered by a more holistic approach to design.

Revisiting the acoustical lexicon and refining use of terms such as ‘noise,’ ‘sound,’ ‘silence,’ and ‘quiet’ allows for a more nuanced discussion of occupants’ needs and expectations, and fosters opportunities to improve the design of the built environment through a proportional exchange between the measure of attenuation and the control of background sound.

Architectural acoustics

Images courtesy KR Moeller Associates Ltd.

The study of acoustics dates back thousands of years. Given its roots are deeply entangled with those of mathematics and physics, it is unsurprising that the typical approach to acoustic investigation is quantitative. Consideration of ‘soft’ parameters (i.e. subjective and descriptive) is relatively scarce until the last century.

Interest in evaluating human response to acoustics gained momentum in the 1900s, with the rise of architectural acoustics, also known as building or room acoustics. Notably, contributions from Bell Telephone Laboratories, Bolt Beranek & Newman Inc., and others have formed the foundation for psychoacoustics, a branch of psychology focusing on the perception of sound and its physiological effects. Research examined occupants’ assessment of the intruding noise (e.g. annoyance, distraction, inadequate acoustical privacy) in their environment.

Motivated by the need to develop an objective approach to effective architectural acoustical design, renowned acoustician William Cavanaugh et al. published Speech Privacy in Buildings (1962), asserting neither acoustical privacy nor acoustical satisfaction could be guaranteed by any single design parameter. This work was instrumental in what later became to be understood as the ‘ABCs’ of architectural acoustical design:

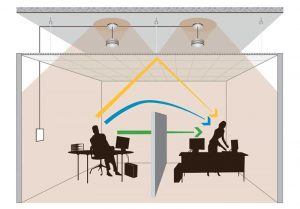

- ‘A’ is for ‘absorb,’ which involves providing sufficient, but not excessive, absorptive materials, in order to reduce the amount of sound energy within the space;

- ‘B’ is for ‘block,’ which involves providing sufficient isolation within the space; and

- ‘C’ is for ‘cover’—or one might say ‘control’—which involves management of the spectral distribution and overall level of background sound within the space, with the intention of masking speech and noise (rather than, for example, adding biophilic sounds, with the intention of increasing the building occupant’s connectivity with the natural environment).

Although the authors of Speech Privacy in Buildings appreciated the importance of background sound, they tended to use the words ‘noise’ and ‘sound’ interchangeably—a practice deeply rooted in historical habits, and continues today.