INDIANAPOLIS — Some place, somewhere in the United States is experiencing drought conditions today. It’s become a constant part of life in America. Plumbing manufacturers have been under pressure from the Environmental Protection Agency to keep reducing the amount of water used by plumbing fixtures, and much work remains to retrofit old, water-hogging plumbing fixtures.

Even with these efforts, the nation’s water supply has been under stress, making alternative water supplies attractive. One of the simplest and most obvious of these alternative water supplies is rainwater capture and reuse.

“Rainwater catchment is one of the oldest and simplest ways of expanding the supply of fresh water. All that is needed is a surface to collect the rainwater, a cistern to collect the stored water in, and a means to distribute the water, writes E.W. “Bob” Boulware, P.E., in his book, Alternative Water Sources and Wastewater Management. “At its simplest, rainwater can be collected in a rain barrel and distributed with a bucket. Larger, more sophisticated systems, supply military bases and resort hotels. As the demand for fresh water expands to parts of the world that previously have not experienced water shortages, rainwater collection promises to be increasingly recognized as an approved supplement to conventional water sources.”

Bob Boulware, P.E. M.B.A., has become one of the country’s preeminent experts on alternative water sources. President of Design-Aire Engineering, Indianapolis, Boulware sits on the Board of Advisors of the International Rainwater Harvesting Alliance, Geneva, Switzerland, and is the past national president of the American Rainwater Catchment Systems Association. Anything that you read in the model codes about rainwater capture and reuse, whether it’s in the International Association of Plumbing & Mechanical Officials Green Code Supplement or the International Code Council’s International Green Construction Code, has been guided by Boulware’s input.

The first step in selection of a rainwater collections system is to determine how much water is needed, Boulware notes. The average United States citizen uses approximately 100-gal. per day for drinking, bathing, waste removal (i.e., flushing toilets) and washing clothes. By comparison, United Kingdom citizens use 87-GPD; Asians use 22-GPD; and Africans use 12-GPD. At a minimum, people need about 2/3-GPD to survive, which represents a pretty wide gulf between the water we need and the water we use. Of note, for a typical developed world application, only about 12% of this total demand actually needs to be potable water. The rest is used for laundry, toilet flushing and personal hygiene. Supplementing potable water needs with rainwater presents an opportunity to significantly reduce the need for utility provided water.

In his book, Boulware notes that many uses don’t need potable water, especially in commercial buildings that may include ultra-low flush water closet fixtures, urinals with electronic flush valves, laundry needs, spas, swimming pools, landscape irrigation, and other recreational options. While the kitchen needs potable water, loads such as these can use lower-quality water and can be separated from the facility’s domestic water system. Hotels add some complexity to the calculations due to the inclusion of showers in the water demand load.

Boulware includes the formula for calculating how much water you can get from a roof surface. The equation is Surface Area (Square Feet) = Demand (Gallons) / (0.623 x Precipitation Density (inches) x system efficiency). Briefly stated, an inch of rain yields 0.623-gal per square foot of roof. After that the tank must be sized to match up, as well as possible, with building water demands and rainfalls amounts, attempting to have enough stored water to accommodate needs during dry spells.

But even residentially, rainwater can be used for both potable and non-potable purposes.

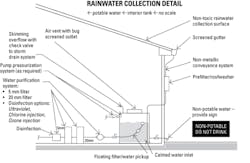

Rainwater that will be used indoors for potable purposes should go through a 20-MM filter, then a 5-MM, and then through a purification system that can use ultraviolet light, or ozone injection, or chlorine injection. It optionally can go through a carbon filter. Since the rainwater collection tank, whether it’s indoors or outdoors, is non-pressurized, the indoor potable section must include a pressure booster pump.

Boulware sketches out a variety of residential schematics for putting together a rainwater collection and reuse system, depending on what the rainwater will be used for and whether that system needs to be freeze-protected. Cisterns in warm-weather climates can be placed outside on a structural pad. The cistern would need to be buried below the frost line in cold weather climates.

Keep in mind that eventually everything that goes into the tank settles to the bottom as sediment, creating what is called an anaerobic zone. In the absence of oxygen, this layer decomposes with the byproducts being methane and SO2, which will add odor and a disagreeable taste to potable water. For better quality water, the water is typically drawn from 4-in. to 6-in. above the bottom of the tank, which is as close to the bottom of the tank that you can get without getting into the anaerobic zone. If the cistern will be used for non-potable water, water can be drawn right from the bottom of the tank.

Boulware’s book, Alternative Water Sources and Wastewater Management, approximately 350-pages in hardcover, is available new from Amazon for $38.07 including free shipping.