The U.S. State Dept. is wading into environmental waters to address British Columbia mining pollution that affects a watershed in northwestern Montana, after a wastewater treatment plant intended to remove pollution appears to have worsened the problem.

“We’re glad to see the U.S. pushing B.C. to do better in regulating water pollution,” says Robyn Duncan, executive director of the British Columbia environmental group Wildsight. “It’s going to take a lot of pressure for B.C. to start taking this problem seriously.”

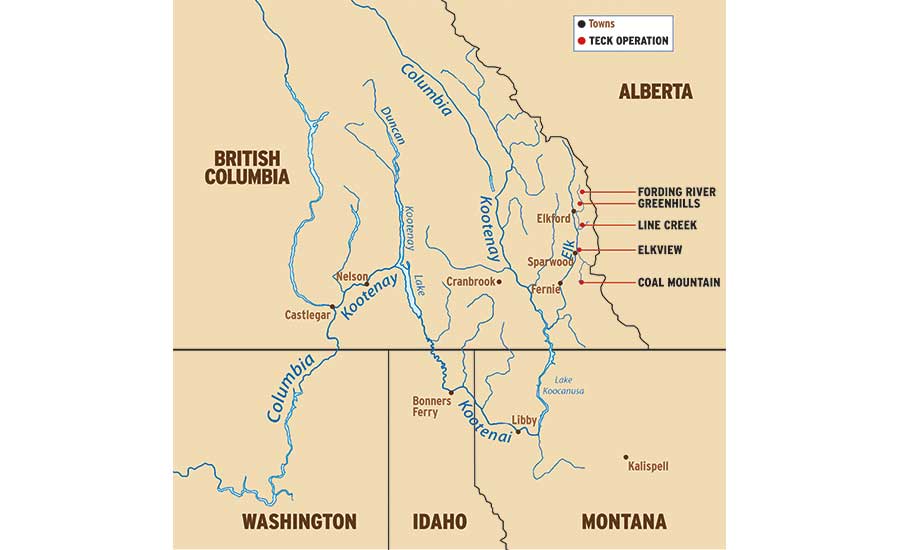

At issue are growing concentrations of selenium, a substance that is leaching from coal-mining waste from five mines along tributaries in British Columbia’s Elk Valley and accumulating downstream in the transboundary watershed of the 485-mile-long Kootenai River and 90-mile-long reservoir Lake Koocanusa. A growing body of evidence suggests that escalating levels of the metal-like selenium could pose a threat to organisms in the aquatic food chain on both sides of the border, including westslope cuthroat trout.

Current British Columbia guidelines recommend no more than 2 micrograms of selenium per liter of water, while the EPA recommends no more than 1.5 micrograms. A 2013 study by the University of Montana indicated that selenium levels downstream of the five coal mines in Elk Valley were 10 times greater than naturally occurring levels in water.

The potential impact on Montana’s economy and public health prompted Gov. Steve Bullock (D) and U.S. Sen. Jon Tester (D-Mont.) to write Secretary of State Rex Tillerson in November seeking State Dept. help. “A strong bilateral water quality standard, developed with British Columbia, is the first step in communicating and protecting Montana’s water quality needs,” Bullock and Tester wrote.

In a January response, the State Dept. said it is committed to addressing the concerns. Tester’s press secretary, David Kuntz, notes that the agency’s action is unusual because it marks an agreement between the department and just one state, Montana, although the department may soon engage with another state bordering British Columbia, Alaska, over similar concerns.

The State Dept. said it will lead a review process with interagency, tribal and stakeholder input and share findings from the review with Global Affairs Canada at the April 2018 International Joint Commission (IJC) meetings.

As a transboundary issue, “The State Dept. is the appropriate arm of the federal government to take a look at this,” says Dave Hadden, director of Bigfork-based conservationist Headwaters Montana. “Whether IJC picks it up from there remains to be seen.”

In 2013, the British Columbia government acted to address mine pollution, ordering Vancouver-based mine operator Teck to reduce selenium and nitrates in the Elk River and nearby tributaries.

Teck responded with a $600-million Elk Valley Water Quality Plan, which included the construction of water treatment plants at each of its five open-pit truck and shovel mines. Upon the 2014 commissioning of the first facility—the $120 million West Line Creek River Plant—a malfunction resulted in the deaths of several dozen trout, leading to a temporary shutdown and a $1.425-million fine. No other plants have been built. (All figures are in U.S. dollars.)

The plant reduced selenium to acceptable levels, but some of the selenium became a more concentrated version of the pollutant. Teck announced plans in 2017 to take the facility off line to perform remedial measures involving “advanced oxidation processes.”

However, the shutdown was contingent upon a government review, and it remains unclear whether the plant is completely off line. A spokeswoman for Canada’s Ministry of the Environment couldn’t comment on whether the plant was on line, and Teck did not return calls for comment.

Numerous industries have supported chemical and biological treatments for selenium that occurs in wastewaters, says Dave Dzombak, head of civil and environmental engineering at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Mellon University. One biological treatment involves packing a column reactor with granular, activated carbon, which supports bacteria to reduce aqueous forms of selenium, Dzombak says. However, the efficacy of plant treatment over a period of decades is questionable because selenium leaches very slowly, creating a potential centuries-long challenge.

“Water treatment is a short-term, energy-intensive fix,” Duncan says. “The only solution we can trust for centuries is to change waste-dump construction practices so that selenium doesn’t leach into our water in the first place.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment