Professor Janis Birkeland is an honorary professor at the University of Melbourne who has taught sustainable planning and architecture at several universities. Previously, she worked as a planner, architect, and lawyer in San Francisco to gain insights into the impediments to sustainability. The following are her thoughts about green buildings and the rating systems that score them.

Despite greater efficiencies and more greenery, buildings increasingly consume energy and resources, forget the poor, and cannibalize the natural life-support system. If all new buildings were “sustainable” by today’s standards, their cumulative impacts would destroy the earth, unless population and consumption rates were magically reversed, not just reduced.

Since 2002, I have contended that truly sustainable buildings would create net public benefits to over-compensate for their (currently) unavoidable material flows and embodied impacts. It is no longer enough to “do no harm”.

Fortunately, buildings can give back more than they take by creating social and natural life-support systems or “eco-services” that increase environmental and social justice in the region (the public estate) and increase nature and wilderness (the ecological base), in absolute terms.

Rating tools were, in part, adopted to head off the growing imposition of onerous environmental impact assessment in the building sector via “industry self-regulation”. Instead of quantifying impacts and sustainability outcomes, green building organizations created prescriptive rules, point systems and thresholds. These were based on typical construction, not sustainability outcomes. Despite the recent adoption of more “positive” adjectives, green building rating tools are still primarily aimed at efficiency: the reduction of waste.

“Net” signifies a whole-system analysis, so one cannot just count gains and ignore losses or vice versa. However, that is what green building and rating tools do, by using selective accounting. For instance:

- Some count positive social impacts without deducting negative ones. Hence, a pristine island converted into a retreat for pedophiles could get a big star if it includes enough social amenities and communal facilities.

- Some tally negative environmental impacts only after mitigation measures are deducted. Hence, design teams start with a typical building template and add mitigation measures that hide “design failures” (for example, pollution, land clearing, embodied energy).

- Some claim to achieve “zero” energy when they only count operating, not manufacturing, energy. Then they label renewable energy sent offsite “positive” even if, in effect, it subsidizes continued coal production or energy wastage elsewhere.

- Some call recycling all construction waste “zero waste”, by ignoring the nature laid to waste during resource extraction.

Green building organizations have been remarkably successful by many indicators. For instance, the adoption of rating and marketing tools by developers continues to snowball, green buildings are gaining prestige, and some tools now advocate the use of life cycle assessment and building information management systems to make design more technocratic.

However, rating tools, like urban design guidelines, still ignore many core socio-ecological sustainability issues (such as ecology and ethics), they measure the wrong things in the wrong ways, and are superimposing a cookie cutter approach to building design upon once diverse sites, environments, and social contexts. Is this really progress? The answer is: only if progress means weak sustainability. This can only delay the destruction of nature and, in turn, society. Greener growth is the old paradigm of “industrial development” in a camouflage outfit.

Progress in Positive Development is expanding positive public options by increasing nature and justice against genuine sustainability standards, rather than current conditions. For progress in the social domain, some point to how rating tools now aim to enhance the well being of owners and occupants, which goes beyond reducing energy and health-related costs for owners.

However, they only make the well-to-do better off. Indirectly, greener growth consigns the poor to more inequitable living conditions as part of the machinery of wealth concentration and class segregation (with exceptions).

For progress in the environmental domain, some point to how rating tools now aim to restore degraded landscapes and create biophilic decors. Some do this by allowing “extra” development (code exemptions) in exchange for offsets such as preserving land elsewhere. While commendable, this is still tokenistic – not eco-positive. The world has lost 60 per cent of its biodiversity in 40 years. Developed land cannot really be restored to pre-settlement conditions with buildings on it, and preserving land does not increase total ecological carrying capacity.

When rating tools were first developed in the 1990s, net-positive impacts were deemed impossible, due to the vestiges of the nature-versus-development dichotomy. (For young readers, this was the idea that “industrial progress” was pre-ordained, so destroying nature was necessary.) Since net-positive impacts were not a goal, no one tried to measure them. Since they were not measured, they could not be managed, so the whole idea was resisted by the management class.

Rating tools purport to improve things, but this is compared to what might have happened if nothing else was tried. This is known as the ‘decoy effect’. Buildings look better when juxtaposed with bad design instead of Positive Development standards (beyond zero).

Sustainability must be recognized as a systems design problem, not simply a matter of “making better choices”. Current design tools and guidelines are really only creativity stimulators, such as “lists” of design principles arranged in a mandala. “Build back better” does not cut it.

Rating tools are called design tools, but they are neither really design nor impact assessment tools. They are decision tools. Decision making helps to make choices between technologies, products, or processes, but is inherently reductionist, if not binary. It does not help create things that never existed before.

“Design”, in Positive Development, means thinking upstream, downstream, laterally, and vertically to find positive synergies through multi-functional and adaptable spaces and structures. Rating tools seldom count multi-functional public benefits created by design synergies, because only listed actions can receive points and they usually only count in one category.

There are many examples of building components and design concepts that can, in combination, be eco-positive – rather than simply regenerating the spaces leftover around ordinary green buildings. Some examples include:

- Green Scaffolding, an exoskeleton that creates ecological space (unlike green facades that add a layer of leaf litter).

- Bricks made from mycelium that sequester waste and carbon yet use little land to produce (unlike agri-waste or hemp-based materials).

- Playgardens that provide a wide range of ecosystem services and community benefits (unlike gardens that only provide biophilic amenities).

Having taught sustainable design from 1992, I realised that people would not accept the idea of net-positive sustainability until it could first be demonstrated and verified in a completed construction. However, my lame efforts at funding the project were met with “you have to show us where it has been done before”, or “we were keen, but then we heard our city already had a green building”.

Second, net-positive must be measured, which traditional environmental impact and life cycle assessment does not yet do. Therefore, in 2010, I proposed a tool for measuring and visualizing cumulative and tributary socio-ecological impacts.

However, I was generationally incapable of making the app myself. So, years later, I found someone who could do it, Dr Ivan Corro. The result is an interactive collaborative game in which a design team competes with itself to create the most sustainable design possible.

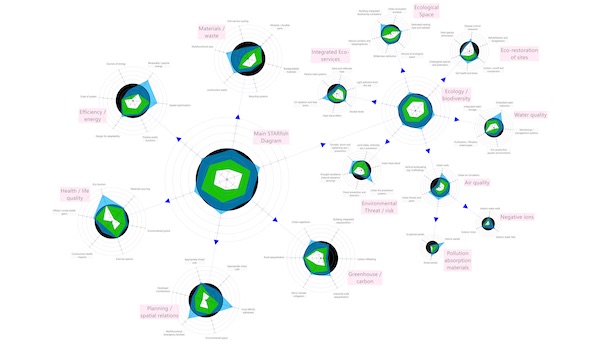

The key to assessing net impacts is a unique combination of radar diagrams and impact wheels, to enable the visualization of life cycle and supply chain impacts. To measure “beyond zero” impacts, it uses a “zero circle” in the middle of the radar diagrams. It provides benchmarks for negative, restorative/regenerative, and positive/net-positive impacts, benchmarked against fixed, regional, and/or pre-urban biophysical conditions (versus contemporary buildings, conditions, or practices).

The diagram could expand in a fractal pattern to cover large-scale, complex systems. For instance, a 3D STARfish hologram could represent a whole industry or city.

The app is just one of the logical outcomes of Positive Development theory. The books include a community planning process, a constitution for eco-governance, a set of forensic planning analyses and a community design review process. These are design-based and ethics-led approaches. They are transformational, rather than transactional. Net-positive Design and Sustainable Urban Development (2020) reviews the necessary paradigm shifts.

Professor Janis Birkeland’s books Positive Development (2008) and Net-Positive Design (2020) explain the theory behind the STARfish tool. The website has written instructions, and the app also has pop-up instructions. The easiest way to see how to use the STARfish is to watch the video on the website.

You can read the original article at www.thefifthestate.com.au

Want to fix housing it’s simple mix pumice cement and water mix and pour into a set of reusable forms

It’s that simple

I doubt that pumicecrete would rate very well with most green building Rating systems because of the high embodied energy of the components.