By David E. Sacks

In the 20th century, wall assemblies discretized into multi-layered systems with each playing a distinct role. Each new layer arose with the emergence of building science technology, including rain screen design principles and the evolution of building materials. What began as an assembly of one primary material offering thermal mass, weather protection, and aesthetics, fragmented into a series of components, including cladding, thermal barrier, air barrier, vapor retarder, weather resistive barrier, and separate structural wall.

Over time, designers developed various wall configurations to provide thermal mass and weather protection suitable to particular building and climate parameters. Building codes ultimately canonized each wall assembly layer, creating prescriptive requirements for the construction industry.

Driven by economics and construction material development, the 21st century brought about an inversion to this trend. Today, there are a plethora of multi-functional material options, including structurally insulated panels (SIP), insulated metal panels (IMP), and integral weather barrier sheathings, all of which reduce the number of discrete layers to limit field labor. They improve quality control while compressing construction schedules.

Foam plastic insulation manufacturers realized the physical performance of their products presented an opportunity to capitalize on their existing characteristics beyond just thermal properties. The origins of this trend emerged in the 1970s and 1980s when manufacturers and trade organizations promoted features such as fire exposure behavior of certain polyisocyanurate (polyiso) insulation boards to eliminate the need for a thermal barrier. This was marketed as a differentiator between polyiso products and XPS products.

When modified and/or accessorized properly, the same insulation board providing thermal resistance may serve as an air, weather, and/or vapor barrier. Select Foam Plastic Insulating Sheathing (FPIS) products merge all barriers and the wall sheathing into a single layer; these FPIS systems are the focus of this article.

All-in-one products pose drawbacks, as well. Difficulties may arise due to multiple factors, including the inherent nature of foam plastic as a combustible material, the lack of structural capacity, the suitability of the FPIS substrate when detailing transitions, and the potential for dimensional instability. Additionally, by their very nature, all-in-one products lack redundancy; a failure in one component creates a full assembly failure.

Background

Insulating Sheathing, as defined by the International Energy Conservation Code (IECC), is an insulating board having a minimum thermal resistance of R-2 of the core material. Foam Plastic Insulating Sheathings (FPIS) simply use foam plastics as an insulating sheathing.

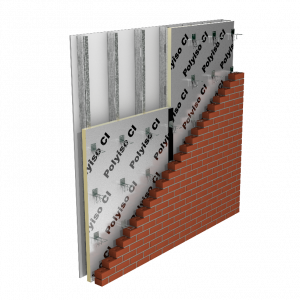

FPIS systems most commonly utilize expanded polystyrene (EPS), extruded polystyrene (XPS) or polyiso insulation enhanced with appropriate facers to create multifunctional products for use in an exterior wall envelope (Figure 2). This article examines polyiso products due to their broad market adoption as an efficient, multi-functional barrier (thermal, air, weather, and vapor) and wall sheathing. Here, efficiency refers both to thermal performance relative to other common insulation types and the related material properties enabling polyiso to serve multiple wall enclosure functions, thereby minimizing necessary wall assembly thickness.

There is a direct correlation between building energy code requirements and the depth of a conventional wall assembly. A 20th century cavity wall would typically include a cladding system (e.g. brick masonry), a 25.4 mm (1 in.) air space, and a wood or steel stud backup wall system, with all insulation provided in the backup stud wall cavity. As energy code requirements become more stringent, a conventional wall provides limited options to comply. Prescriptive code requires exterior continuous insulation (i.e. insulation outboard of the backup stud wall); this improves the entire wall thermal performance and also enhances cavity insulation performance, which is otherwise diminished due to thermal bridging effects at studs, especially steel studs.