by Viken Koukounian, PhD, P.Eng., and Niklas Moeller

Given the intense focus on health and safety as well as the changes in work/life balance precipitated by the COVID-19 outbreak, it is not surprising the pandemic has accelerated the healthy-building movement and the ‘people-first’ mindset spearheaded by standards such as WELL and Fitwel. There is burgeoning consensus that buildings need to be designed with deep commitment to the well-being of their occupants.

Effective acoustics are key to healthy buildings. After all, noise is known to provoke physiological stress responses that can negatively impact occupants. The World Health Organization (WHO) describes it as an “underestimated threat” contributing to stress, high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, dementia, and diabetes. Therefore, WELL and Fitwel take acoustics into consideration; however, it remains a poorly understood indoor environmental quality (IEQ) parameter, and the lowest rated (referenced from ‘Green buildings and health,’ Global Environmental Health and Sustainability, vol. 2, 2015, by G. J. Allen, P. MacNaughton, J. G. Cendeno Laurent, S. S. Flanigan, E. S. Eitland and J. D. Spengler).

Returning to the workplace

Low scores have added significance in today’s climate. Many employees found a silver lining in the ways in which stay-at-home orders enriched their family lives, even as the scope of their work and social lives contracted. As companies start to bring—or attempt to draw—them back to the office, occupant satisfaction is more important than ever. Organizations need to implement strategies to not only keep staff safe and healthy, but also happy and productive enough within their working environment that they actually want to come in.

Amongst the architecture and design community, there is growing conviction these goals must be achieved through concern with ‘equity’—and applied to ‘real-world’ needs such as acoustical privacy, rather than amenities like pool tables, private chefs, and other perks; in other words, it is more a matter of how employees are treated than what they are being treated to (for more information, read Talitha Liu and Lexi Tsien’s article in ‘The Office as We Knew It No Longer Exists,’ Azure, September 2020).

Images courtesy KR Moeller Associates Ltd.

Firms such as Gensler point out that although employees are enjoying benefits (e.g. more time with family and less spent commuting) while working from home, many are also struggling with less-than-ideal conditions (e.g. poor internet connectivity, shared workspace with children and other family members, noisy neighbors and neighborhoods) that negatively impact their engagement and productivity. Whether an organization wants their office to be occupied fulltime post-pandemic or to serve as a critical part of a hybrid working model, it has the potential to act as a ‘great equalizer’—a shared facility that is specifically designed to support employees’ work and overall well-being.

According to the 2020 Gensler Work from Home Survey, 88 percent of employees would like to return to the workplace in some capacity. One of the primary reasons the 2300-plus participants cite is the need for a quiet, distraction-free environment—a desire echoed by the 32,000-plus people polled during studies Steelcase conducted across 10 countries. It is clear acoustics matter and, therefore, are vital to ensuring employees not only enjoy equal access to the facility itself, but also to the IEQ parameters that are needed to work comfortably and effectively.

The question is, what is ‘acoustical equity’ and how does one achieve it?

The sound that actually exists

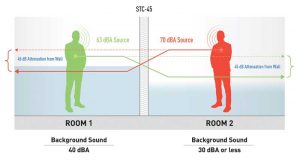

En route to answering these questions, one must first consider the traditional approach to acoustics, which relies on ‘categorization’ and ‘acceptable-level’ schemes prevalent throughout building standards and codes. The former specifies sound-rating values (e.g. sound transmission class [STC], noise isolation class [NIC], impact isolation class [IIC], ceiling attenuation class [CAC]) for the boundaries of a room or building envelope, while the latter uses noise-rating values (e.g. noise criteria [NC], noise rating [NR], room criteria [RC]) to set maximum limits for noise, such as those generated by building systems, services, and utilities. However, neither offer insight into the ‘actual acoustics’ (i.e. the sound actually present) within a space or occupant experience of it.

To improve results—a goal that one can, with a broad brushstroke, call ‘better acoustics’—and fulfill the objective of designing with occupants in mind, one must turn their attention to the sound actually present in a space and look at it through the lens of both architectural acoustics (i.e. the study of sound and its behavior in and due to a space) and psychoacoustics (i.e. the study of the psychological and physiological effects of sound and its perception). Indeed, one cannot be separated from the other, as psychoacoustical evaluation of a space considers the outcome of the combined performance of all acoustical features.

Is this information somehow also applicable to the construction of public elementary schools?