by Harry Lubitz, CDT

There are two types of flood-proofing—dry and wet. Dry flood-proofing implies a new design for a structure or retrofit additions to an existing facility that prevents the entry of flood waters. This includes proactively avoiding lower openings or permanently sealing them, retrofitting waterproof closures to lower openings, or providing temporary waterproof membranes or barriers to block flood water intrusion. A common, last-minute dry flood-proofing technique is to wall in the structure with sand-bags, thereby blocking rising flood waters.

Wet flood-proofing, on the other hand, involves an intentional design process to allow water to enter a structure built with flood-resistant materials like masonry. The design intent is to permit flood waters to enter and exit the structure freely and enable the flood waters to rise and fall evenly inside the building in the same rate and manner as on the outside. This also implies the flood-resistant materials are a permanent part of the structure. They can be maintained to provide an attractive look before a flood event, and can also be easily restored to their original condition at minimal cost.

Images © FEMA

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) provides numerous documents to assist the design and build of both dry and wet flood-proofed structures. The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) 24, Flood Resistant Design and Construction, is referenced in the International Building Code (IBC), and recognized by FEMA to “meet or exceed the national minimum National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) requirements for buildings and structures.”

The U.S. Congress established NFIP in the National Flood Insurance Act (NFIA) of 1968 with the objective of providing communities and property owners cost-effective flood insurance options, guidance for floodplain management, and set design and construction standards to protect buildings constructed in special flood hazard areas (SFHAs). These regulations and standards are found in Title 44 of the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations. NFIP’s ultimate goal is to minimize and insure losses due to flood events.

NFIP creates maps to identify SFHAs on the basis of a “base flood,” which is defined as a “flood that has a one-percent chance [of] being equaled or exceeded in any given year (commonly called the “100-year” flood).” These maps establish the base flood elevation (BFE). NFIP regulations require all construction below BFE use building materials that are “flood damage-resistant”.

NFIP defines these materials as “any building product [material, component, or system] capable of withstanding direct and prolonged contact with floodwaters without sustaining significant damage. The term “prolonged contact” means at least 72 hours and “significant damage” refers to any damage requiring more than cosmetic repair. Cosmetic repair includes cleaning, sanitizing, and resurfacing (e.g. sanding, repair of joints, and repainting of the material). The cost of the repair should also be less than the replacement of affected materials and systems.”

It is important for the specifier to pay close attention to the regulations for flood damage-resistance materials as it may have a direct impact on the structure’s ability to withstand and recover from flood damage and impact the cost of NFIP flood insurance.

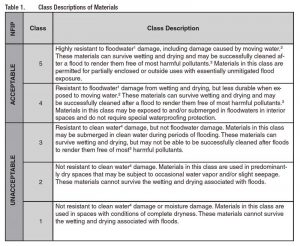

Flood damage-resistant materials are based on the five class descriptions shown in Figure 1. Virtually, all masonry materials are Class 5 flood damage-resistant materials (Figure 2). It is important to note concrete blocks can potentially act as holding vessels for floodwater should the exterior skin be breached. This would make it difficult or impossible to clean the blocks. Therefore, design professionals should take great care in specifying a water-resistant envelope for concrete blocks used in various wet flood-proofing activities.

Solid elevated walls

As masonry has been identified as a flood damage-resistant material, it is optimal for elevating a structure above BFE. Figure 3 shows options—two of which are masonry—to meet the minimum requirements if the lowest floor is at BFE. The foundation wall is typically extended to the height of a full story, which could be higher than the BFE, to create storage or parking areas. These elevated walls provide a consistent look with other structures in the area. While it is required to use flood damage-resistant materials below BFE, the author strongly recommends employing the same material on any construction below the lowest floor.