Drones have only seen limited use in New York City for construction documentation and facade inspections due to restrictive local ordinances. But that may be changing with the release of a new report from the New York City Dept. of Buildings, which sees future potential for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV), or drones, to be used in building facade inspections.

"Our report is the product of intensive research by DOB experts and finds that when combined with traditional hands-on examinations, the effective use of drones could potentially result in more comprehensive building inspections, resulting in reduced inefficiencies and a safer New York City,” said NYC Buildings Commissioner Melanie E. La Rocca in a press statement about the report's release.

Under current New York City regulations it is not legal to fly drones freely over the city. Drones can only land or take off from designated areas near airports, heliports and certain public parks, and visual line-of-sight is required for an operator to pilot a drone. These and other restrictions have meant that drones are only legally used in the city under specific circumstances or with prior approval.

In 2020, the city passed Local Law 102, which required the NYC DOB to study the use of drones to conduct facade inspections in conjunction with hands-on inspections.

Hurdles to Adoption

The resulting report, "Using Drones to Conduct Facade Inspections," outlines the current state of drone inspection technologies and the many hurdles to adopting them for facade inspections within New York City. Growing usage of drones in other industries in recent years has spurred the city to consider the issue, but the report found the available technology still falls short of meeting all the requirements for performing building facade inspections.

Specifically, the report highlights the limits of drone photography as a potential replacement for human vision. “The most common output format from drones is two-dimensional images, specifically photographs. High resolution images can still mask the extent of defects by flattening the viewpoint, and even videos may miss critical angles that an inspector may need to determine whether there is a significant defect and its extent or underlying cause,” the report states. In further examination of the topic, the report found that inspectors working off of drone imagery could potentially miss defects that were visible to inspectors working at street level or at height. Usage of LiDAR, laser-scanning or thermal-imaging devices mounted on drones is referenced in the report, but was not fully evaluated.

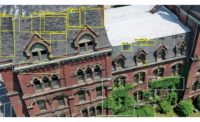

While the report doesn’t see drones replacing human building facade inspectors any time soon, it does see potential for the technology as a way to identify problem areas ahead of in-person inspections. One possible side benefit of using drones for a sort of “first-pass” facade inspection is reducing the amount of sidewalk sheds and scaffolding needed before in-person inspections. “For example, instead of providing a sidewalk shed at two faces of a building, the drone inspection, after being evaluated by the [facade inspector], may demonstrate that a shed is only needed at a portion of one face of the building,” the report states. While this is only a hypothetical situation, it does offer one way that drones could speed up inspections in the city, where erection and maintenance of sidewalk sheds and scaffolding have been a point of contention for years among safety advocates and building owners.

But despite the potential for drones to aid in facade inspections, the report concludes that there is simply not enough available data on drones being used for facade inspections to offer a judgement either way just yet. While there is some precedent established for drone use in construction, the report notes that “in construction, drones are most commonly used to gather data from large sites to assess progress and not necessarily to identify finer details.”

Additionally, NYC DOB researchers found few instances of drones being used for facade inspections in other U.S. cities, even in places where drone usage is more widely permitted. Drones have been used for inspections of critical infrastructure such as bridges and rail trestles, but their use for building facade inspections remains rare, the researchers write. “Without more concrete information, any benefits or increases to public safety from the use of drones remain incalculable.”

The report ultimately recommends further study of the issue before any action is taken, but does concede that drone use is continuously expanding, and “the City will want to investigate additional rules or guidelines needed to ensure public safety in the future from a wide range of perspectives.”

While the report was relatively guarded in its recommendations, the industry response has been positive so far. “Today is an important step towards the potential deployment of this new tool by professional engineers to increase public safety,” said John Evers, president and CEO of the American Council of Engineering Companies of New York, in a statement released alongside the report. “We look forward to working with DOB to make sure drone technology is used appropriately and effectively.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment