Former U.S. Dept. of Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx grew up on “the wrong side of the tracks.”

“My home was a stone’s throw from Interstates 85 and 77,” recalls Foxx, who grew up in Charlotte, N.C., and served as DOT Secretary from 2013-17 under President Barack Obama. “The airport was nearby. Planes flew at low altitude over our house. Whether or not I was using the system, I sure heard and saw a lot of it.” Desirable areas to live were far away from transportation infrastructure, “and the property values of those living near these projects was diminished.”

The era of interstate construction was often shaped by blatantly racist practices such as redlining. According to author Richard Rothstein, in 1933, faced with a housing shortage, the federal government began a program explicitly designed to increase and segregate America's housing stock. He told NPR in 2017 that the efforts were "primarily designed to provide housing to white, middle-class, lower-middle-class families." Rothstein said that Blacks and other disadvantaged sectors of the population were left out of the new suburban communities — and pushed into urban housing projects.

Rothstein noted that the Federal Housing Administration, which was established in 1934, furthered the segregation efforts by refusing to insure mortgages in and near African-American neighborhoods — a policy known as redlining. At the same time, the FHA was subsidizing builders who were mass-producing entire subdivisions for whites — with the requirement that none of the homes be sold to African-Americans.

But sometimes it wasn’t that blatant. When deciding to build a project, it was about “how to do this quickly and who’s least likely to complain, which were poor and Black communities,” Foxx says. Informed by his own experience, Foxx as DOT Secretary “began to think about how could we put in place a mechanism that would be more fair, and could we design projects in ways less negatively impactful on areas they touch. That was during a time when we were mostly using executive authority. The toolbox for me was very limited.”

Times are changing. The Biden administration and DOT Secretary Pete Buttigieg have emphasized social equity as a key component of transportation policy. This month, Buttigieg announced that $905.25 million will be awarded to 24 projects in 18 states under the Infrastructure for Rebuilding America (INFRA) discretionary grant program. For the first time in USDOT’s history, criteria for winning these grants included how they would address climate change, environmental justice, and racial equity.

Former U.S. Dept. of Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx

Headshot courtesy of JTR Strategies

In a June 29 press conference in Syracuse, N.Y., Buttigieg addressed the role I-81 construction in the mid-1950s played in harming a Black neighborhood, wiping out the 15th Ward. “Racial justice cannot be separated from transportation,” he said. “The planners behind it often routed it in a way to do lasting damage to Black communities.” (read more about the environmental justice of the I-81 project here)

New York State is moving forward with a draft environmental impact statement for a $2-billion plan that might include removing 1.4 miles of bridges on I-81 and rerouting traffic to I-481 on the city’s eastern side. The project will emphasize hiring local residents.

WSP has created a dedicated equity services line with a strategic approach to projects.

*Click the image to see the infographic

Graphic courtesy of WSP

A Disappointing History

This focus was a long time coming, says Fred Wagner, former chief counsel of the U.S. Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and partner with the law firm Venable. “The history of trying to consider equity in transportation has been rather disappointing,” he says. “The Clinton administration’s Executive Order on Environmental Justice dates back to 1994. Between then and now, the types of things that have been accomplished were more in the realm of the informational, like community outreach. That’s good, but didn’t really get to heart of the question of how best to provide an equitable transportation system.” Wagner expects the federal environmental review processes moving forward will emphasize alternatives that can meet equity concerns. For example, “if there’s a project that’s more auto-focused, are there any mitigations to assist those who use transit? If building a highway or toll facility, you might mandate that it’s free for buses or van pools.”

Contractors and engineers should not fret that there might not always be a specific billion-dollar highway or transit project, he adds. “There will be a billion dollars’ worth of [work]—with a strong equity component,” says Wagner.

Arup is already working on these kinds of projects, says Kate White, planning policy leader in its San Francisco office. For example, Arup conducted an equity study for planned express toll lanes in San Mateo, Calif. “It was cutting-edge in terms of looking at equitable outcomes for tolling projects,” she says. The firm surveyed communities regarding transportation access and mobility needs, and how tolled revenue should be used to address those needs.

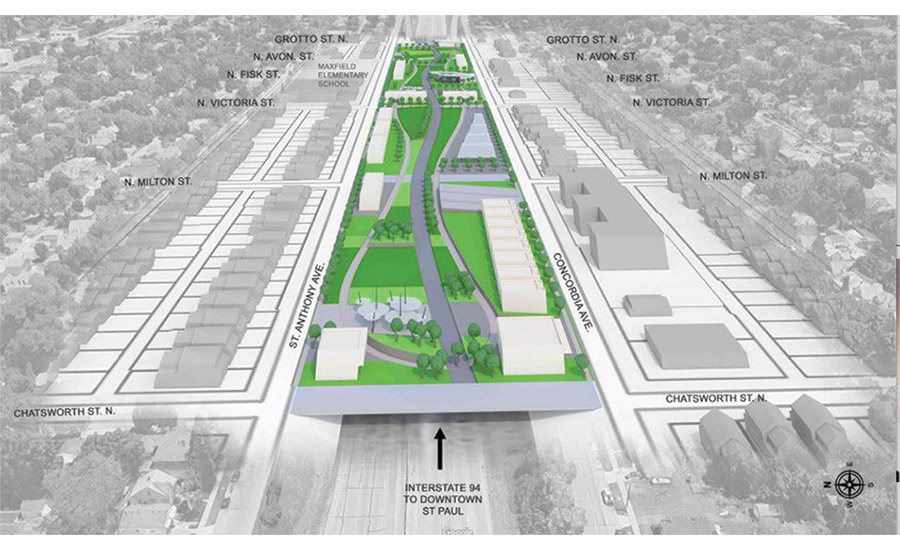

Discussions are underway to address the harm to a Black neighborhood in Rondo, Minn., caused by the construction of I-94. A land bridge is proposed.

Photo courtesy of Streets MN

Recommendations include using toll revenue to provide discounted transit passes and discounted tolls for low-income residents.

Other firms also are focusing on equity, even including it in specific job titles. Gabi Brazzil, for example, is a WSP project manager focusing on equity in project delivery. “The philosophy for me and WSP is thinking more about what we do than just a job title,” she says. “In terms of the industry, I think there is better organization around equity.”

The Portland DOT is looking at capping I-5 through Rose Hill, Ore., to make room for economic development. The plan would also widen the highway.

Rendering courtesy of Portland DOT

Not Just Checking the Box

The emphasis is on intentional inclusion of stakeholders who historically have been left out of the conversation, Brazzil says, adding that in the past three years, “clients have been specifically calling out equity in requests for proposals. Public engagement is not just checking the box. It’s about talking with communities, not at them.”

She cites complete streets projects “where we have proposed creating advisory groups representing the diversity of that community, providing public services to help sustain them and compensating them for their output.”

That is the case with ConnectSF, a multi-agency effort in San Francisco planning long-range transportation projects and policies that “correct past harms and prioritize the needs of people of color, underrepresented groups, and people who rely on our transit system the most,” says Erica Kato, a spokesperson for the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. “ConnectSF designed its community workshops around including groups that are often underrepresented in transportation planning. This included targeted workshops in the Bayview neighborhood, as well as workshops specifically for youth.”

“[PROJECTS] WILL NOT BE CONSIDERED A SUCCESS JUST BY BEING BUILT. THEY NEED TO CONNECT COMMUNITIES AND CREATE SUCCESS.”

— VERONICA SIRANOSIAN, AECOM

During the pandemic, the team offered payments to community organizations “who could help us reach constituents with limited internet access, non-English speakers, and others who face obstacles engaging with online outreach tools,” she says.

But weighing the potential disruptions of a proposed project on communities versus the potential need for and benefits of that project can be complicated.

The FHWA this year paused a $7-billion reconfiguration of I-45 through downtown Houston, pending an investigation into concerns under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and that environmental justice issues were not being considered. The North Houston Highway Improvement Project has been in the works since 2011. It would rebuild a 26.4-mile-long portion of I-45 from downtown Houston to Beltway 8 in three segments. Work would add four managed express lanes and reroute I-45 to parallel I-10 and US 59/I-69, while realigning sections of I-10 and US 59/I-69 to eliminate roadway reverse curves. The project would move below ground level US 59/I-69 between I-10 and Spur 527 south of downtown, and add bicycle/pedestrian path along the 44 downtown streets that cross the freeways.

In its final environmental impact statement released last August, the Texas Dept. of Transportation wrote: “Segments 1, 2, and 3 of the NHHIP are 87%, 83.5%, and 73.6% minority, respectively, as measured by adjacent Census block groups. Similarly, 10 of the 17 super neighborhoods in the study area are predominantly minority. Adverse effects from the proposed project would be experienced.”

Shawn Wilson, Louisiana Dept. of Transportation and Development Secretary

Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee (D-Texas), Air Alliance Houston and community organization Texas Housers subsequently sent letters to TxDOT detailing concerns under Title VI and related to environmental justice. In February, however, TxDOT released a record of decision. Plans were in place to begin construction as soon as this year.

But in response to the letters, which were forwarded to FHWA, division administrator Achille Alonzi on March 8 asked TxDOT to pause work while FHWA reviewed those concerns. Harris County also filed a federal lawsuit against TxDOT. At a March 11 press conference, Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo said traffic volume on I-45 has been increasing since 2008, and noted the $2.8-billion widening of the I-10/Katy Freeway actually increased commute times for about 85% of drivers.

“Like many highways in the past, [the project] will have significant impacts on neighborhoods and businesses, particularly low income neighborhoods. The communities that were divided to build I-45 have had no voice in this and no voice in how the initial highway was created,” Hidalgo said.

Bob Kaufman, a TxDOT spokesperson, told ENR in a statement: “It’s unfortunate there is an expanded delay on this project, but TxDOT remains fully committed to working with FHWA and local officials on an appropriate path forward. We know that many in the community are anxious to see this project advance.” TxDOT’s environmental impact statement says the agency has attended more than 300 stakeholder meetings.

A project that includes capping a highway aims to revitalize a Pittsburgh neighborhood (top ↑); a Houston highway expansion (rendering below ↓) is paused due to social equity concerns.

Rendering (top)courtesy of Gensler, rendering (bottom) courtesy of TXDOT

Oregon’s ‘Clash’

Another example of an attempt to rectify past harm is Portland, Ore.’s Rose Quarter project. Nearly 122,000 vehicles crowd through a 1.7-mile section of I-5 through the Rose Quarter. With no shoulders, the four-lane segment offers little room for motorists to weave and merge safely, resulting in near-constant congestion and a crash rate 3.5 times higher than any other section of urban interstate in Oregon.

Surrounding the slog of traffic are historically Black neighborhoods that have struggled since being cleaved by construction of I-5 in the 1960s. Local media reports have played up a “clash” between the Oregon Dept. of Transportation’s desire to widen the stretch versus community groups wanting the highway capped. But it doesn’t appear to be quite so black and white.

ODOT project director Megan Channell says the agency has adopted a community involvement approach that is “more relational and responsive to social justice needs and community input.” Efforts to shape the project’s overall vision included regional and neighborhood-level surveys, focus groups and an advisory committee to inform project design, she says.

They’ve coalesced into a plan to add an auxiliary lane and 12-ft shoulders in each direction, most of which ODOT hopes can be incorporated with minimal right-of-way acquisition. ODOT plans to replace several bridges over I-5 with steel and concrete highway covers, creating community spaces and a catalyst for future redevelopment.

The construction manager/general contractor team, led by Hamilton Construction Co. and Sundt Construction Co., includes local contractor Raimore Construction, which will coordinate efforts to achieve 18% to 22% Disadvantaged Business Enterprise participation—which would be the highest for a transportation project in state history. Design is scheduled to reach the 30% stage later this year, at which time ODOT will reevaluate the current $715- to $795-million estimated cost. Construction could begin as soon as 2023.

Channell is hopeful the Rose Quarter project will not only reunite a long-divided Portland neighborhood, but provide a model for similar complex projects around the state. “We have a lot of lessons learned already, and more learnings to go,” she says.

Not Black and White

Even in Syracuse, which Buttigieg touted as a poster child for efforts to rectify wrongs, the answer isn’t straightforward.

The $2-billion project to replace the I-81 aqueduct aims to repair the multigenerational economic and health damage caused by the original construction. Displacement of Black residents resulted in the “irreversible loss of property and business ownership, access to jobs, and social and community connections,” says the New York Civil Liberties Union in “Building a Better Future: the Structural Racism Built Into I-81, and How to Tear it Down,” a December 2020 report.

“What’s eerily similar” between the current and “original project was, the people did speak out. It was still built despite the outcry,” says Lanessa Owens-Chaplin, an assistant director at the New York Civil Liberties Union, who co-authored the report.

Regarding Buttigieg’s press conference, the NYCLU “put out an alert to let people know they would be there,” she says, to ensure state and federal officials “know people who care are going to show up” at meetings about the project and its impacts.

“PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT IS NOT JUST ABOUT CHECKING THE BOX. IT’S ABOUT TALKING WITH COMMUNITIES—NOT AT THEM.”

-GABI BRAZZIL, WSP PROJECT MANAGER

Community members have plenty to be wary about, according to the NYCLU report, which outlines problems with the New York Dept. of Transportation’s current draft design report and draft environmental impact statement released in April 2019. The next draft report and EIS is slated to come out late July or early August. The public will have 60 days to read and comment, and government agencies hope to have a final draft in January 2022. After studying options like a new viaduct or an underground tunnel, the preferred alternative is currently the “community grid.” New roadways would disperse traffic through the city grid, include new pedestrian and bicycle amenities, and create a new business loop dubbed “BL 81.”

The current preferred alternative isn’t perfect. One of the troubling aspects is a highway ramp that would be just 250 ft from Dr. King Elementary School. According to the Centers for Disease Control, ramps should be at least 600 ft from children because of pollution-related health issues.

Another issue is land use. After the project is completed, the area will become “prime real estate,” Owens-Chaplin says, but rather than see it gentrified, the community wants residents to have priority over large businesses and market rate-paying tenants. The neighborhoods are slated to be rezoned to high-density commercial zoning, from residential and light industrial. “It’s almost like the city of Syracuse is getting ready to commercialize this area,” she says, rather than build family-friendly residences and small businesses.

As in Syracuse, Pittsburgh planners are hoping a redevelopment effort will foster social healing in the city’s Lower Hill District by reconnecting that area to the rest of the Hill District and downtown.

Surface parking lots currently occupy the area that will be turned into a mixed-use development anchored by a park. The development is intended to build a more inclusive community through a new mini-neighborhood that will provide a gateway into the Hill, near the city’s hockey arena.

In the 1960s, when the now long-gone Civic Arena was built, city planners razed a section of the Lower Hill District—a historically Black community—with promises the area would be redeveloped. It never was. Now, with a new arena, a 28-acre redevelopment is set to break ground this month. It will be anchored by a new $220-million headquarters for FNB Corp.

That’s just the first phase of the revitalization led by the Pittsburgh Penguins in cooperation with Pittsburgh’s Urban Redevelopment Authority, FNB Corp., and the developer, Buccini Pollin Group. PJ Dick is the contractor. The project will also reconnect the Hill District to Downtown with an I-579 cap under construction. That project, slated for a fall completion, will feature a park atop the Crosstown Expressway. The FNB project will be under construction into 2023.

The urban grid destroyed in the 1960s razing was rebuilt, with plans for public open space in one section that will include a series of terraces and pathways serving as a transition up the Lower Hill. Diamonte Walker, deputy director of Urban Redevelopment Authority, is upbeat about the project. “It is important to me that we root ourselves in history but simultaneously ensure that we are bending the arc of prosperity towards present-day Hill District residents,” she says. “I am a fifth-generation Hill District resident, so I am invested both personally and professionally. The preservation of the existing culture, and the inclusion and manifestation of the vision of current Hill stakeholders is significant and valuable.”

Pittsburgh Penguins chief operating officer Kevin Acklin adds: “We are pursuing an overall $1-billion development which attracts an injection of private capital investment into the center of the city, and will generate thousands of immediate construction jobs and thousands more permanent jobs.”

But can these efforts really heal old wounds?

“Nothing can erase [those past] mistakes,” says Acklin. “But we are committed to restorative development that creates jobs for the neighborhood and tax revenue for the city and region.” The Penguins have worked with the community for more than a decade to invest in the neighborhood and create a strong M/WBE program, he says.

Railing for Justice

Constructed in the late 1890s as a bypass around Atlanta’s congested downtown rail lines, the 22-mile BeltLine helped fuel area growth for half a century. Factories and warehouses sprang up along a route that, in many locations, deliberately established or reinforced class and color divisions. By the 1950s, rail traffic began to give way to vehicles and Atlanta’s suburban sprawl.

Though the BeltLine’s heyday was relatively short-lived, its racial, social and economic impacts endured. While some neighborhoods prospered in the ensuing decades, others—particularly poorer, predominantly Black areas—were constrained by the abandoned alignment’s barriers to mobility and economic development.

Building upon a graduate student’s proposal to convert the BeltLine right-of-way into a ring of trails and parks, a public-private collaboration has worked since 2005 to reconnect neighborhoods while promoting inclusive growth and civic engagement. Commercial and residential development in the surrounding tax allocation district, which helps fund the BeltLine’s planned 25-year, $4.8-billion buildout, includes mandates for affordable housing and D/MBE participation.

The Metropolitan Atlanta Regional Transit Authority recently launched a six-month feasibility study for incorporating light rail transit in the corridor, including a proposed 2-mile extension of the existing Atlanta Streetcar. “The fact that low-income and people of color in Atlanta tend to have a greater reliance on transit underscores the need to ensure the addition of transit on the BeltLine corridor,” says Nonet Sykes, chief equity and inclusion officer for Atlanta BeltLine Inc., the non-profit overseeing the redevelopment program. While the BeltLine has made significant progress in reconnecting neighborhoods, Sykes admits the challenge of achieving the project’s full vision is formidable.

“WE’RE ... DEVELOPING A WORKFORCE THAT LOOKS LIKE THE PEOPLE WE WORK FOR.”

-ROGER MILLAR, WSDOT SECRETARY

“We understand that dismantling inequitable policies and practices is complex and will take deliberate and sustained action,” she says. That includes ensuring the BeltLine has sufficient funding before its dedicated tax expires in 2030. Recently, the Atlanta City Council approved creation of a special tax district that will provide some $100 million to complete the trail loop and help Atlanta BeltLine Inc., access philanthropic contributions, grants and additional sources.

Gaining philanthropic support from leaders of local businesses was key to the Smart Columbus, Ohio, initiative, which received a $40-million grant via the Smart Cities program under Foxx’s tenure. The program also received $10 million from Vulcan Inc., the investment firm led by Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen, to promote electric vehicles, grid modernization and other goals.

The Columbus Partnership, a nonprofit organization made up of 75 CEOs of private-sector employers, also committed $90 million. “[Columbus Partnership president and CEO] Alex Fischer got CEOs on board and got businesses to commit to buying electric vehicles and installing charging stations,” notes Katie Ott Zehnder, technology department leader with HNTB. Regarding Smart Columbus’s goal of improving mobility for disadvantaged communities, “I hope it becomes a norm that transportation technology is seen as a solution,” she adds.

Reconnecting Rondo

Public-private-philanthropic partnerships may be key to Reconnect Rondo, a nearly $500-million vision to cap I-94 and create a Black enterprise district in Minnesota, said Keith Baker, Reconnect Rondo executive director. In a Transportation Research Board webinar, he noted even a light rail system built in the 2000s negatively affected Rondo, going right past it to Minneapolis.

But transit agencies can play a major role in improving mobility equity and justice. Veronica Siranosian, vice president of digital innovation for AECOM, says the Chicago Metropolitan Association for Planning’s long-range transportation plan acknowledges the spotlight the COVID-19 pandemic put on transportation and racial equity. “We did a case study review of what other agencies are doing,” she says. “One was LA Metro’s rapid equity assessment tool,” developed in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests, during which Metro controversially suspended service that stranded essential workers. Buses were used by law enforcement to transport protesters.

Major infrastructure projects “will also be done in a different way as opposed to a physical built-in focus only,” notes Siranosian. “There will be a heightened emphasis on the fact that these are happening within communities who need to be involved. They will not be considered a success just by being built. They need to connect communities and create success.”

One of the ways to do that is by having leadership that comes from those communities. Shawn Wilson, Louisiana Dept. of Transportation and Development secretary, will be the first Black president of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. “This is an opportunity to target the issues of pathways to equity and partnering to deliver,” he says. “Now is the time to address them head on in a productive and positive way.”

The Washington state Dept. of Transportation is also attempting to do that. WsDOT secretary Roger Millar recalls, “I was given a clear direction that a top priority was addressing inclusion. We’re working on developing a workforce that looks like the people we work for.”

Last year, in the wake of COVID-19 and the Black Lives Matter protests, members of the Western Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials formed a committee to work on a systemic racism resolution. The group took the resolution to AASHTO’s strategic management committee. AASHTO adopted it.

“We can’t sit around as a bunch of white, wealthy, abled people and decide what these communities want,” Millar says. “They have to be at the table.” Still, planned projects will be controversial. “We have a lot to learn, but we acknowledge that and are putting our best effort into it,” Millar says. “It’s going to be ugly at times—but not as ugly as doing nothing.”

With Jonathan Barnes, Eydie Cubarrubia, Jim Parsons and Louise Poirier

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment